The AI crisis in SEO is the latest iteration of a long-running trend

Organic marketing is far from "dead", but a website-centric content marketing model alone may no longer sustain it

The expansion of AI results in Google search, and the resultant decline in click-through rates (CTRs) and organic traffic, is leading many people in the industry to question the fundamental assumptions that underpin SEO:

Is website traffic still a meaningful goal? Should we be trying to do something else? If so, how do we measure that something else?

I think these are important questions, and asking them is long overdue. The approach to SEO built largely or entirely around website-centric content marketing has been under threat for a long time. Large language models (LLMs, like ChatGPT or Google’s AI results) are just the latest in a series of developments that herald a different — and, for most practitioners, uncomfortable — kind of organic marketing.

But you can always rely on the SEO industry to chase the shiny new thing (and give it an unwieldy initialism). And so, to many SEOs, Google search is now “dead” (always dead, never just “declining” — far too pedestrian), and the new concern is GEO, or AEO, or AIO, or LLMAO (no, me neither).

But LLMs are a nascent technology with an uncertain future. Although often impressive, their influence could be curtailed in any number of ways, from copyright lawsuits to user apathy to the commercial imperatives of their creators (Google won’t harm their cost-per-click to gain AI market share forever — will we still want AI when it’s full of ads?).

To bet the farm on “optimising for AI”, then, is to gamble on hype1. And, assuming LLMs do play a big role in the future of search, they’ll be just one of many platforms through which people make decisions about what to buy.

Instead, I think the wisest response to organic marketing’s most recent, and probably biggest, crisis is to pay attention to principles — the broader shifts in user behaviour — rather than platforms. To recognise that the web is a more fractured place, its users less trusting than ever of big tech platforms, and that brands need to be visible on whichever channels their target audience seeks answers to their problems, not just on their own websites (although for many brands, this will continue to be a vital marketing channel, as will traffic referred by Google’s search engine).

This is not easy to do. It demands new methods of measurement and attribution, an overhaul of standardised ideas of “SEO services”, and resources from teams SEOs aren’t used to working with. Many in the “search everywhere optimisation” boat have been glib about how it actually works in practice, gesturing vaguely at promising ideas without recognising the inherent limitations and challenges of these more novel platforms, and ignoring the difficult reality for marketers who have to sell this stuff to their bosses and clients.

But ultimately the brands that turn this crisis into an opportunity will be the ones who add another “layer” to organic strategy — before keyword research, technical SEO or content planning — that asks “is my website still the best way to try and engage my audience as they search for answers in organic channels? And if not, what is?”

“Brands as publishers”: a model for the “ten blue links” era

The term “brands as publishers” came into vogue around 2012 or 2013, judging from search results. The idea behind it was that brands would stop thinking about selling and instead use “content marketing” (which at this point was still a novel concept) to build audience loyalty in the manner of a media company. 2012 was the year the Guardian published their guide to “effective content marketing strategy”. In 2013, they analysed “why brands are becoming publishers”. (Econsultancy would wonder what this phrase “really means” a year after that.)

Early content marketing efforts were largely high-cost, high-quality investments by brands that had the budget and the clout to do something special and genuinely memorable. It was hard to measure, and therefore hard to justify in strict commercial terms, but digital platforms made it possible for brands to have vast reach, and some of them were willing to push the limits of that reach.

2013 was also the year the great Doug Kessler wrote “Crap: the single biggest threat to B2B content marketing”, in which he foresaw the inevitable end result of this novel phenomenon: everyone and their mum jumping on the bandwagon and producing an overwhelming deluge of content ballast. (Everything Doug predicted applies to B2C content marketing, too.)

Crap aged like a fine single malt. Content marketing is now ubiquitous, a complete given, and even small businesses have dedicated editorial teams (which is still quite weird, when you think about it).

As it grew less unusual, content marketing became more measurable, more disciplined; a performance channel rather than an experimental venture. The notion of “distribution strategy” became central, within which the two primary channels were: search engines, where steady demand and 0 marginal costs promised compounding (if slow-burn) returns; and social media platforms, which provided short-lived traffic spikes to complement the slow, steady chuntering of SEO.

But over the years, the big social media platforms — especially Facebook — sent less and less traffic to websites, and the notion of social as a channel through which to redirect your audience to your owned platforms quickly tailed off. Nowadays, nobody sensible evaluates their social media strategy purely by the amount of traffic it sends to their website.

For search engines, the decline in traffic was not so clear or linear. For every search engine results page (SERP) feature or ad display that crowded out organic results, Google sufficiently grew its total query to compensate, which meant that, in absolute terms, most websites got more and more traffic.

But as a proportion of total search volume, Google has sent less and less traffic to the open web every year for nearly a decade (at least)2.

Most sites never noticed, but still — like every other platform, Google has been choking off traffic to the open web for a long time and prioritising keeping users on Google. And this threatens the standard SEO model, which measures success largely in terms of how many people get to your website.

That model was necessary and self-evident in the “ten blue links” days. Back then, organic discovery happened almost entirely through Google search. And Google search consisted of links to websites, which meant you had to have a website to be visible on the web, and you had to populate it with lots of content to target various search queries.

Google results no longer consist of just links to websites. Even before the AIO explosion that hammered everybody’s organic traffic, search results were a smorgasbord of ads and search features. For the most popular queries, organic results have been barely visible for some time.

At the same time, audiences have adopted alternative platforms for online research. In March 2024, SOCI released a well-publicised survey that suggested 18-24-year-olds used TikTok “as a search engine” — that is, instead of Google search.

Reddit, too, has exploded in popularity, with millions adding “reddit” to the end of their Google queries. SEMrush estimates that, in January 2023, the total monthly search volume of queries containing “reddit” was around 4 million. By December, it was close to 12 million.

Apart from being a damning indictment of Reddit’s search functionality, it shows that online searchers, frustrated by broad-brush search results that don’t address their query, are looking for genuine answers from specialised communities.

Seeing this trend, Google responded. User-generated content (UGC, like Reddit, Quora, specialist forums) is dramatically more visible in search results than it used to be3. One of the most significant implications of March’s algorithm update was a major increase in the number of queries for which UGC sites rank in the top 3.

Using Ahrefs data, here’s Reddit:

And Quora:

It’s not just huge, global UGC platforms either. Here’s Shopify’s forum (which I’ve chosen for the highly scientific reason that I happen to have been analysing it recently for a client):

And here’s the forum of MoneySavingExpert, a popular financial advice platform in the UK:

Web users, now less trusting of organic search results, are increasingly doing their research on other platforms. Often, they’re turning to smaller online communities to get genuine insights. They may still be navigating to those communities via Google, but they’re not open to a wide range of sources in the way they perhaps were.

In February of this year, The Verge commissioned a survey that reached similar conclusions. Their press release declared “The future of the internet is likely smaller communities, with a focus on curated experiences”.

Why the shift away from googling and clicking on websites? There could be many factors. A big one appears to be the ever-growing prominence of ads, and the greater difficulty of distinguishing between what’s sponsored and what isn’t.

Others will blame the SEO industry, also with good reason: the very phrase “SEO content” implies quickly-produced pieces that largely copy existing results and avoid originality by design. (Deep down in our hearts, we all know this “content” has not made the internet a better place.)

We could also blame specific changes to Google’s algorithm. Most updates give evermore prominence to big brands, and heavy-handed query rewriting leads to broad results that don’t solve more precise queries4.

Whatever the reasons, the key point is this: Yes, AI overviews in search results have had a sudden and explosive impact on the effectiveness of “traditional” SEO, and prompted many to radically overhaul their SEO strategies. But longer-term shifts in audience behaviour have been hollowing out those strategies for years.

Nowadays, people make their decisions about what to buy in much more fragmented ways. Their research may take them from Claude, to Reddit, to YouTube, to a tiny forum you’ve never even heard of, and then finally to Google, where, having done exhaustive research elsewhere, they type in your brand name and navigate to your site to make their purchase5.

These research patterns are likely complex, non-linear, and highly variable between individuals. Everyone will have their own way of combining the available platforms into a satisfying experience, and the platforms we use will come and go6.

But we can be pretty confident about what people aren’t doing much anymore (if they ever were): starting with a google search, landing on your blog post, being guided through a “funnel” that is entirely within your control, and then making a purchase7.

And yet, the corporate website, which is now often a much smaller part of the organic equation, is still where the most SEOs focus all of their attention. As a consequence, they risk having a trivial influence on their target audience’s buying decisions (and therefore trivial influence with their bosses or clients).

And so it’s good that Google’s big AI investment is causing people to rethink whether website traffic is a worthwhile metric. But such metrics have been questionable for a long time, and if your answer is to focus your efforts entirely on “optimising for AI”, you’re missing the broader principle: the process of organic discovery on the web is now complex and fragmented, and while AI can be really important, it’s only one part of the mix.

Is your website an asset or an assumption? A new “strategic layer” for organic marketing

I would suggest a better response to all this uncertainty is to add a new “strategic layer” to your organic marketing strategy, one that asks “is our website going to be the place our target audience looks for answers to their problems online? Is it where they will make decisions about what to buy?”

Sometimes the answer will still be yes, sometimes it will be no, sometimes it will be somewhere in-between. Much of this will depend on the “model” of SEO your website uses and the way your audience searches.

For example, marketplaces may continue to find their website is the best way to engage their audience organically. If I want to compare, say, holiday rentals, the range of properties, filtering options and smooth booking process offered on the Airbnb website is a much better medium than going on Reddit and asking if anybody has rented a nice villa recently.

Similarly, many sites get large volumes of traffic from interactive tools that are difficult or impossible for LLMs to replicate. For example, when I worked at Cuvva, we built an insurance group checker that uses an API to look up a car’s insurance group based on its number plate. You can’t ask an LLM “in which insurance group is the car with the following license plate”.

Again: it’s not about abandoning the website as a strategic marketing tool. It’s about evaluating its usefulness against other platforms, and seeing your owned channels as one part of a fragmented search landscape, rather than treating it as your entire toolkit.

Even content-driven sites that typically rely heavily on steady, search-focused publishing won’t need to abandon content marketing altogether. But it should be more strategic, with a greater emphasis on highly relevant, maybe lower-volume queries that are less dominated by SERP features and not devoured by AI, but are highly relevant to your brand messaging.

The results in those SERPs also tend to look less like over-optimised copies of one another, because nobody’s going after them at scale. This can make users more trusting. My own (pretty limited) research bears this out: aggregating pre-AI Search Console data for 7 clients, I found that CTRs were consistently significantly higher from the SERPs of lower-volume queries (according to Ahrefs data) than higher-volume queries. I suspect this is because popular queries are stuffed with SERP features; unpopular queries often still look like “ten blue links”.

It’s difficult to adapt to changes in organic discovery because novel platforms lack established metrics or “best practice”

In writing this, my intention isn’t to be critical of marketers. I have been as guilty as anyone of sticking with the website-centric SEO model when, on some level, I knew it wasn’t really working.

It is difficult to make this shift in mindset and strategy, especially when your working days are spent mostly in the trenches of day-to-day implementation work. For me, the recent challenge to SEO’s fundamental assumptions has served as a much-needed kick up the arse, forcing me to pay attention to changes of which I’ve long been dimly aware. I suspect many others are in the same boat.

I think there are two main reasons it’s particularly difficult to adapt to foundational changes in organic marketing:

1) it is difficult to measure and attribute success in novel channels,

2) such channels necessitate resources from different departments, which is politically challenging

These challenges – one commercial and one operational – are, in my opinion, the most interesting challenges in organic marketing today. I can’t address them in meaningful detail here, but I want to focus on how they can be tackled in my next few articles. They’re difficult, but far from impossible.

Personally, I’m particularly intrigued by the first one. I’ve long focused on how organic marketing data can be made more meaningful: ours is a discipline awash with data, the vast majority of it noisy, and I don’t think the SEO industry has ever figured out how to really make sense of the numbers. (If we had, “domain authority” and “keyword difficulty” metrics wouldn’t be a thing.)

Those who can think creatively about how we gather and interpret organic performance data across non-owned channels could find themselves in high demand.

Again, this isn’t the place to go into detail – although I will at some point – but there are a number of approaches that jump out to me. Ngram models of relevant high-engagement posts on Reddit or forums to find commonly discussed topics; counting brand mentions via API or a scraper; calculating sentiment scores where the brand name is mentioned and tracking improvements over time: there’s lots marketers can do to prove the value of this kind of work, if we can think about it imaginatively.

Despite the challenges, I really would urge you to think of it as an opportunity. Website traffic might be dropping, but that is a chance to broaden our ideas of what organic marketing is and can do. We can engage with the web as it actually is and as most of us actually use it, rather than doggedly persisting with an often stale set of “SEO processes”.

The question to ask yourself, I think, if you’re now considering changing your approach to organic marketing as a result of AI’s disruptive influence: what would you do if all the AI stuff turned out to be a damp squib?

What if it doesn’t really take off? What if the LLM revolution that’s so readily hyped is crushed by regulation, or hollowed out by the need for greater profitability (do you want ChatGPT with ads?), or withered by court battles over copyright?

Will you go back to treating your website as the sole way to engage with your audience, waving away the clear and compelling changes in organic discovery? Or are you ready to accept that our organic marketing strategies may be out of date, built for an open web model that has been in decline for the best part of a decade, and to adapt to the uncertainty that brings?

And that’s assuming “optimising for AI” is meaningfully different to “optimising for Google” — early research suggests there’s huge overlap between their methods of information retrieval.

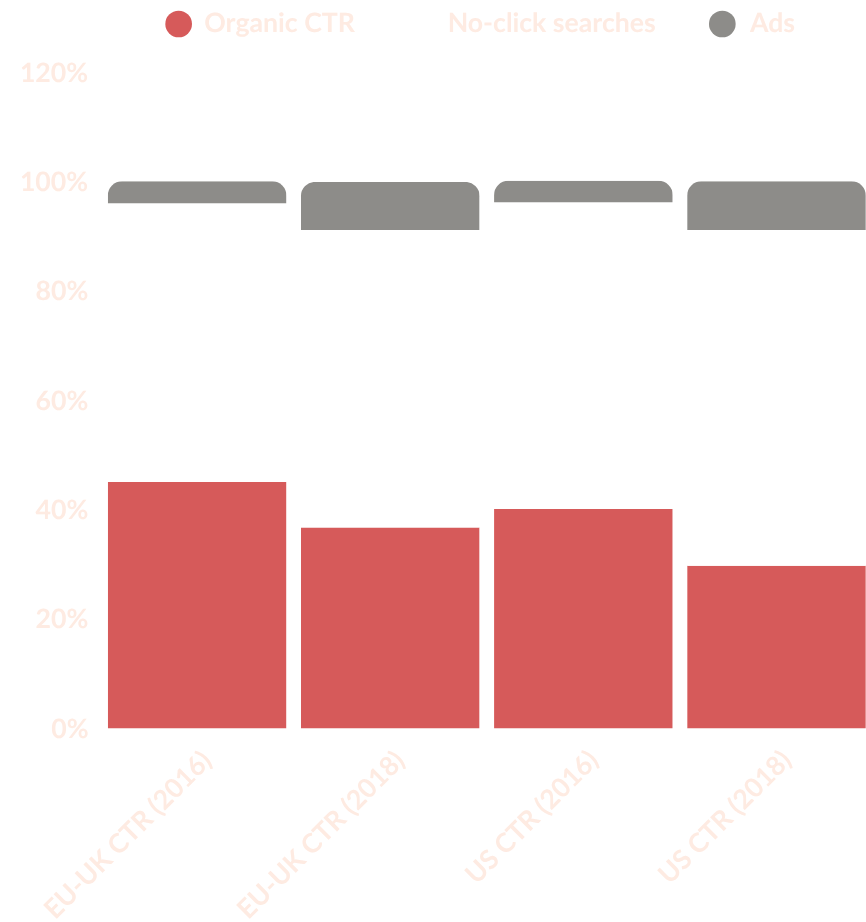

Most data suggests the decline in CTR caused by AI results in Google search isn’t even the biggest CTR drop in recent years. It’s just that, for the first time, Google search isn’t seeing the kind of growth that gives you more traffic in absolute terms.

I remember when the presence of a Reddit or Quora thread in SERPs was a clear sign that Google didn’t have much quality content on the subject. It was my favourite trick for picking out low-competition queries.

It’s hard to get exact data on this, but the Search Engine Journal article linked above notes that 54% of searchers now spend more time digging through search results. SEMrush data suggests around 35% of search refinements are longer than the original query, which would imply searchers are having to rephrase their queries in an effort to get more precisely-relevant results.

There’s a reason most brands get much more homepage traffic from branded queries than they used to. Their audience is making their decision elsewhere and navigating directly to the website as a last-touch point of conversion.

It was not so long ago every other SEO-related blog post was about the transformative impact of voice search. Before then, many SEOs were paying close attention to the growing prominence of Google+ posts in search results. Oh well.

I find this mindset shift easier and more obvious when I reflect on patterns in my own buying behaviour. I do not trust organic results to give me unbiased recommendations. I’m also well aware that the articles have been written “for SEO”, and so are probably authored by a junior agency copywriter who had zero knowledge of the topic before they were asked to write about it that morning. Because of this, I do almost all my product research on forums and Reddit, but often I first get a broad overview of the subject from ChatGPT. If I have few specific criteria, I might also browse Shopping results in SERPs. But I don’t think I’ve ever clicked on “top-of-funnel content” SERPs and directly gone on to make a purchase as a result.