How to meaningfully measure the new organic opportunities

ROI has always been the wrong metric: now that "new" organic channels offer big opportunities, we need better ways to quantify them.

The standard organic marketing KPIs are being questioned like never before, and this is leading many to wonder how to “prove ROI”. I think they’re asking the wrong question: it’s always been essentially impossible to truly calculate the ROI from SEO, even before the great AI-ing.

Most organic ROI calculations ignore its real costs. They look good - and therefore often form the basis of proposals - but they’re simplistic and inflated, which is why so many such proposals are rejected.

Of course, just because ROI is inadequate doesn’t mean demonstrating value isn’t important. But there’s a better way to approach it: quantifying big, broad market opportunities. This is more relevant to the actual goal of organic marketing, which is structured, sustainable, long-term acquisition.

Quantifying opportunity is more challenging than it was: in this brave new world of organic (or trying to be brave at least, with quivering lip), once-widely accepted measures of potential - search volume, traffic - are now questionable.

But I’d argue that the opportunities themselves are greater than they were, thanks to an encouraging (if belated) shift in mentality inspired by these sweeping changes: many brands and marketers are thinking of organic not just as “what does our target audience type into Google?”, but “how does our target audience discuss and research products online, and how can we best reach them?”

Powered by these new ways of thinking, organic is better able than ever not only to deliver direct results, but also to support other channels and business functions. Attribution may be fuzzier, but it’s not impossible. Those brands that find ways to quantify opportunities and measure success will do very well indeed.

Attempts to calculate “organic ROI” typically underestimate costs and overestimate attributable revenues

The standard formula for calculating ROI, which goes:

take revenue from organic search

subtract cost of agency/consultant/salary of SEO team

divide by costs

is so reductive as to be meaningless, for two main reasons:

1) SEOs are not solely (or even largely) responsible for earning organic revenue

Businesses do all sorts of things that boost organic revenue that have nothing to do with SEOs. That revenue doesn’t result from concerted investment in organic, so it shouldn’t be considered a success of that investment.

Brands can account for this by measuring incremental revenue: forecasting what would have happened based on historical trends, and attributing the excess to deliberate organic investment.

2) SEOs are a tiny part of costs

Organic is a consultative discipline: its practitioners usually provide insights and recommendations, and other people - mostly writers and developers - do the real work of implementing. Every minute those people are spending on SEO-related tasks is time they’re not spending doing something else.

This is “opportunity cost”, a concept familiar to anyone who had economics lessons at school.

Most organic marketing costs are opportunity costs. The developer who’s fixing a bug that causes the sitemap to include hundreds of 404s is doing that instead of fixing a bug in the checkout process, or improving an internal dashboard that helps your customer support team resolve tickets faster.1

Both of those tasks would have generated revenue, either directly (fixing the checkout bug so more people can make purchases) or by reducing expenses (if your support team can solve more issues more quickly, you don’t need to hire new support staff).

But our hypothetical developer was fixing the sitemap. So none of those other things happened. That foregone revenue has to be considered a “cost” of SEO.

Organic marketing is about building towards long-term opportunities, not quick profitability: evaluate it based on its broad potential

If we can’t meaningfully measure organic ROI, it makes little sense to use it as an argument for investment. But many marketers do, because they’re convinced by simplistic calculations that “high ROI” is what makes organic marketing valuable.

Not only does this ignore opportunity cost and fail to account for the operational burden of even small organic investments - content needs a briefing process and maintenance plan, dev work needs to be ticketed and validated - it misunderstands what makes organic investment worthwhile: although unpredictable and often slow to deliver returns, it offers steady, compounding, profitable long-term customer acquisition - when you get it right.

In other words, the value of organic is in the big picture: how, through careful strategy and sustained investment, you build a system that generates revenue at no marginal cost. And so, instead of starting with a small-scale set of tactics to “prove ROI”, organic marketing investment should be made - or not made - with an eye on bigger opportunities.

It can be useful to think of it like a product launch. You don’t enter new markets “because it has good ROI”: the inputs are too vague and varied to know that. Instead, you measure the size of the market, how big a slice of it you can win, and what it would take to get there.

In other words, you have to quantify the broad organic opportunity, the resources needed to capture that opportunity, and how you’ll measure progress towards it.

Quantifying the opportunity: from “what’s next?” to “what’s possible?”

Quantifying organic marketing opportunity is highly variable. It depends on your industry, your target audience, and the precise dynamics of how that audience discusses and researches products online. There’s no fixed process, only principles: consider potential over tactics; draw from a range of relevant data sources; be clear about the resources needed and honest about the unknowns.

Here’s a (very) simple illustration of the difference between ROI-driven thinking and quantifying the opportunity, using the example of a SaaS startup considering content marketing to target search queries. It’s based on “traditional” approaches to SEO, and again comes with the caveat this is not a universal process.

A common - but often ineffective - approach might be to spend a few thousand to:

identify a set of keywords competitors are ranking for that you’re not

calculate the gap in their estimated traffic and yours, and extrapolate how much more you’d get by stealing their rankings

infer additional revenue from your historical conversion rates

write those pages

But this is small thinking: does organic marketing, whose results are unpredictable and slow, really have much value at this scale, regardless of its profitability?

Better to look at the size of the market. This doesn’t have to be complicated: you could (and eventually should) do a big deep dive on keyword research, competitive SERP analysis and resource planning, but you could start by checking:

how much estimated traffic an established competitor gets

how they’ve earned it, broadly (how much content do they have? For which queries and topics do they perform best?)

what it would take for you to steal some of that demand (how competitive are those SERPs? Do the same brands rank for all related topics or are there gaps in their content strategy? Do backlinks correlate strongly with rankings or can newer sites win with strong content?)

The analysis itself is as simple and accessible as in the first scenario, but the mindset is completely different: it provides a clear and immediate view of what organic marketing could achieve given long-term, strategic investment, not just how you can get more traffic in the short-term. And it gives you a broad sense of the scale of investment needed - both cash and team resources - without having to try and calculate precise opportunity costs.

For the “new” organic marketing channels - such as large language models, discussion platforms and social media - quantifying opportunities is more challenging, but far from impossible

With the recent and ongoing changes in organic marketing, quantifying opportunity will be more challenging, at least in the short term.

Plummeting click-through rates from Google search have led to a widespread questioning of established SEO KPIs. Many have embraced - wisely and belatedly, in my view - a broader truth: organic discovery on the web is more fragmented, and the idea of a marketing funnel that takes place entirely on owned platforms is, in most cases, spurious.

More brands are recognising the value of social channels, discussion platforms (Reddit and other forums), aggregator sites and large language models (LLMs) as powerful sources of organic discovery. In many cases, these platforms don’t lead directly to website traffic: instead, you see its value in higher branded search, as your audience seeks you out once they’re ready to make a purchase.

This doesn’t mean that organic marketing presents less of an opportunity than it did. Quite the opposite: when the mindset is “how does our target audience research products online, and how can we best reach them?” - rather than “how does our target audience google things?” - the scope is broader.2

But it does make those opportunities harder to measure. Under the website-traffic-centric organic marketing paradigm, metrics like search volume and estimated traffic are widely accepted (even if such metrics are far less precise and authoritative than the SEO tools would have you believe).3

Many are now exploring channels where no such widely accepted KPIs exist (yet). There is no public data about the frequency with which topics are raised on ChatGPT, or the exact language used in relevant prompts. We can read forum discussions in which our brand is discussed favourably, but we can’t (easily) directly measure how much of that discussion turns into branded search or conversions.

Attribution, then, is necessarily fuzzier. We have to analyse trends, make inferences, test hypotheses, monitor uplifts. Data gathering is a little more laborious.

But those brands that get comfortable with the ambiguity and work hard to quantify opportunity will find themselves far ahead of those who pull their investment for the want of a simple KPI.

Bottom-line numbers - new customers, sales, revenue, customer lifetime value - will of course remain the goal. But here are some (slightly surface-level) examples of how platform-specific metrics can be used to quantify opportunity.

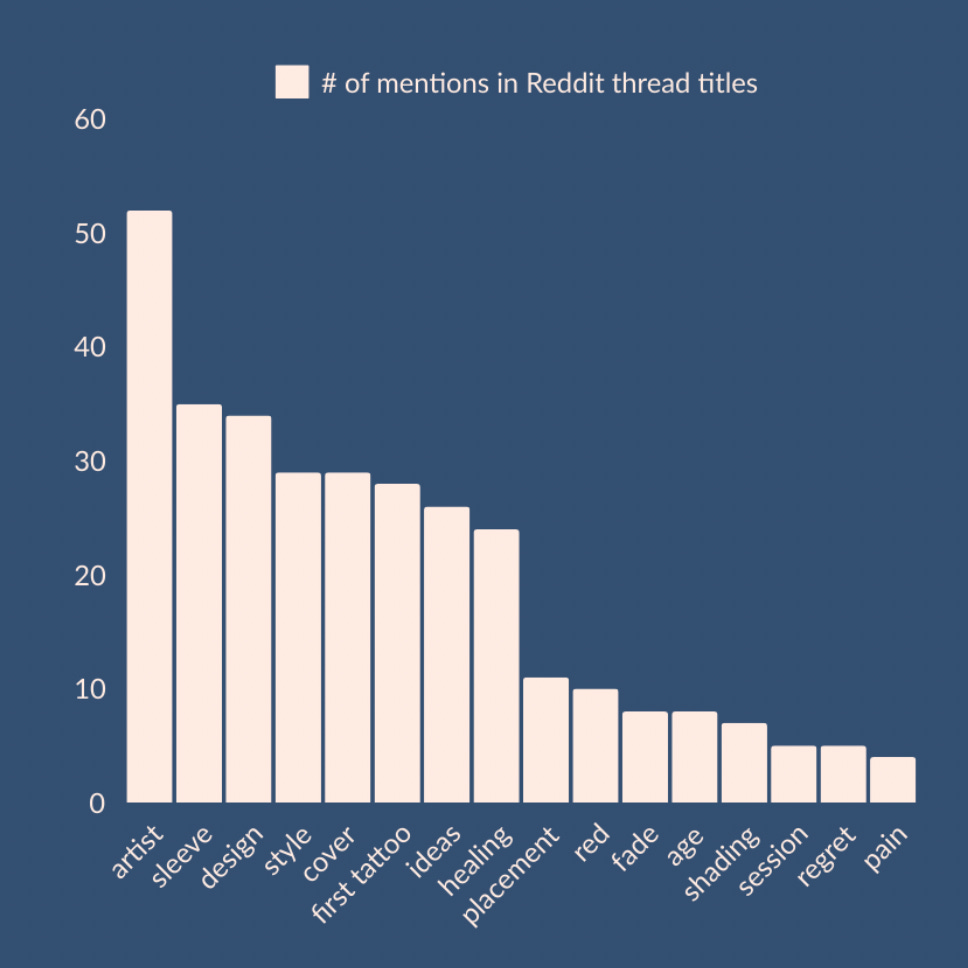

If you want to engage on Reddit, you can:

gather a list of relevant subreddits

create a list of relevant terms to look for on those subreddits (useful if the topic is quite broad) - or just grab the lot

extract relevant threads using an API like PRAW, RedditWarp or snoowrap

build an ngram model from thread titles to find common problems

The number of relevant threads tells you the size of the opportunity - estimate the average work involved in engaging per thread to figure out what resources you need.

If you want to interpret and shape how large language models use your website content to form an understanding your product, you can:

export your website’s log files

filter by LLM user agents

count the pages that are most frequently visited

review and update those pages to promote key messages and remove any inaccurate or outdated information

The number of relevant pages and their quality/up-to-dateness tells you the size of the opportunity - estimate the average work involved in editing them to figure out what resources you need.

If you want to improve brand perception on industry forums, you can:

make a list of relevant forums/UGC platforms

google ‘site:[relevant forum] “[your brand name]”’ to figure out which ones are discussing you

fire up Screaming Frog

use the “custom extraction” feature to grab sentences or paragraphs that include to your brand name

use an LLM or pre-trained classification model like BERT to calculate the sentiment of brand references (and also themes, if that’s your jam)

the number of relevant threads tells you the size of the opportunity - the negativity of sentiment tells you the work involved.

If you want to roughly assess your visibility on LLMs, you can “spot test” by:

gathering a list of threads and topics from forums, as described above (forum queries better fit the longer, more contextual nature of LLM prompts, but admittedly it’s not perfect)

“clustering” those threads and comments into broader “questions” using a model like BERT or ChatGPT

clustering those questions into broader “problems” or themes

feeding each question from a problem into the LLM (this is quicker via API, but it’s possible manually)

extracting referenced sources, prominence of source, sentiment of generated text, key repeated phrases in prompts - whatever’s useful to you

averaging the individual “question” data across the “problem” group

If you want to find highly-relevant “zero-volume” search queries, you can:

mine sales calls transcripts for customer pain points

scrape opinion pieces from trade media and build a topic model of the contents to find emerging topics

input the Reddit and forum data you gathered earlier

build a big ngram model out of the results

use relevant ngrams as seed keywords to find low-competition queries your competitors aren’t after

export all your many keywords

cluster them based on shared search results to get a sense of how much content you need to target all that search demand

The volume of gathered queries tells you the size of the opportunity - the amount of content needed gives you a good idea of the work involved.

(By a remarkable coincidence, I can be hired to help with any of this stuff. Email me if you’re interested.)

These metrics aren’t perfect - but what metrics are - and many take more technical skill to gather than the ones many in organic marketing are used to. But they give shape to uncertainty. Correctly gathered, they can tell you what’s possible to achieve on unfamiliar platforms, and what it would take to achieve it.

Sometimes a well-defined opportunity isn’t enough - you have to make your recommendations “strategically relevant”

There’s another reason organic projects don’t get buy-in: they just don’t line up with a business’s existing priorities.

This is typically a failure in how opportunities are communicated or tactics prioritised. Organic is a versatile channel that provides subtle secondary benefits as well as big performance ones.

Here is an example of how reframing or reprioritising organic initiatives can build confidence and secure buy-in: one of my clients sells their product exclusively through a mobile app. They reached out because they were interested in the potential of SEO to “fill the top of the funnel”. But, because users couldn’t make purchases on the web, conversion rates were too low to justify the allocation of significant resources.

At first, it was difficult to get much buy-in. SEO was always bottom of the list of priorities.

But this client had another problem: once customers made a purchase, they typically uninstalled the app. The biggest challenge my client faced wasn’t acquiring new customers, it was maximising revenue per customer. (No wonder they didn’t want to funnel resources to organic acquisition; ROI was irrelevant here.)

To solve these issues, they wanted to build helpful in-app tools to keep customers coming back. But what to build? How to prioritise? Here, organic was valuable: search volume told us what kinds of problems our target audience had, and building organic traffic to web-based prototypes gave us valuable engagement data.

Another example: a two-sided marketplace earned a steady stream of new users at low marginal cost through organic search. And then they pulled organic investment and removed the pages that brought in most traffic.

They had good reason: the other side of the marketplace was empty, so all these new users I was helping to bring in had nobody to buy from. Organic might have been delivering an “excellent ROI” based on average lifetime values, but it didn’t matter.

To get buy-in, I stopped talking about broad revenue/new customer numbers and made specific recommendations to balance out the lop-sided marketplace.

In both cases, organic marketing was delivering customers profitably, but it was largely ignored until it was made strategically relevant.

Both examples illustrate the problems with using ROI to evaluate organic marketing. It is a blunt instrument that oversimplifies often complex commercial priorities. It makes agencies and consultants look good - which is why many like to reference it - but it doesn’t reflect the peculiar dynamics upon which organic investment decisions tend to rest.

Both stories also show the importance of not just quantifying opportunities, but contextualising them within a wider set of commercial priorities. When a business’s most important initiatives are complemented by the organic opportunity, it justifies shifting some of the resources allocated to those initiatives.

The new frontiers of organic marketing are less confined to the idiosyncratic jargon and byzantine logic of search engine algorithms, and this makes them better suited to being strategically relevant.

If brand perception is important to you - of course it is - calculating the sentiment of Reddit discussions that involve your brand is huge. Especially because many brand teams lack the capacity or technical skill to source such data themselves.

Mining forums for engagement opportunities is a strong source of customer pain points - gold for product development.

Organic marketing, when conceived as an open-ended, all-platform approach to reaching and understanding a target audience, is naturally highly relevant to and complementary of other business functions.

(For the industry, it’s a great chance to shake off a reputation for insularity and opaqueness. But from the number of SEOs recommending “cosine similarity” and “vector index presence rate” as new KPIs, I suspect that opportunity will be squandered.)

So while attribution may be fuzzier, and defining KPIs a little more laborious, the strategic opportunity is bigger than ever. Just don’t try to put it in neat ROI terms.

(If you’d like to follow up on anything discussed in the article - especially if you’d like to work together on implementing these approaches - please email me at hello@kurtlwood.com)

In this respect, SEO is different to paid channels, for which you can throw together a quick landing page, chuck some budget behind a campaign, and see what happens. That’s why decision-makers often pour millions into PPC and ignore SEO, even though SEO is “cheaper”. They understand, better than many marketers, how many internal resources have to be allocated to SEO to make it a success.

It also means more brands can succeed, because they can operate on the most relevant platforms, rather than everything competing for the same zero-sum search results.

These metrics are often wrong, but they are at least useful. They facilitate (pretty rough) forecasting. You can take your average click-through rates at various position, make sketchy estimates about where you might rank for a bunch of new queries, and calculate the percentage of traffic you’d likely get based on total search volumes. You can then take a percentage of that traffic based on historical conversion rates and give yourself a rough objective for new customers based on SEO investment.